Introduction

In the field of proteomics, researchers are constantly searching for new tools to dissect protein interactions and functions. In this regard, protein arrays are powerful tools because they offer a high-throughput method to analyze thousands of proteins simultaneously. These arrays consist of purified proteins immobilized on a solid surface, enabling the study of protein-protein, nucleic acid-protein, enzyme-substrate interactions, and antibody specificity on a large scale [1].

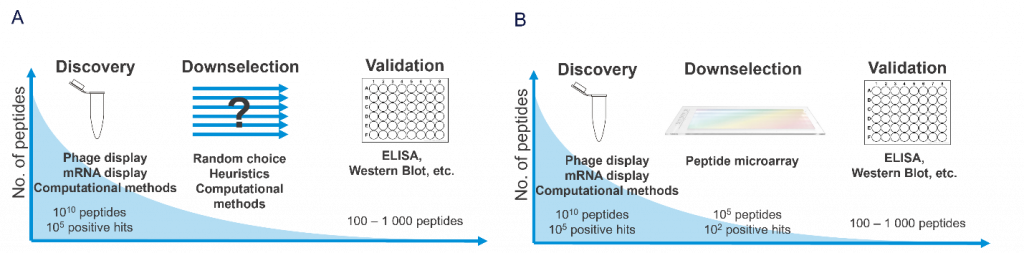

Peptide arrays, on the other hand, use short sequences of amino acids and have become important for projects associated with epitope mapping, investigating protein-peptide interactions, and identifying specific binding sites within proteins [2].

While both protein and peptide arrays are important tools in research and development, they possess distinct characteristics that make them uniquely suited for different aspects of proteomics research.

Protein Arrays

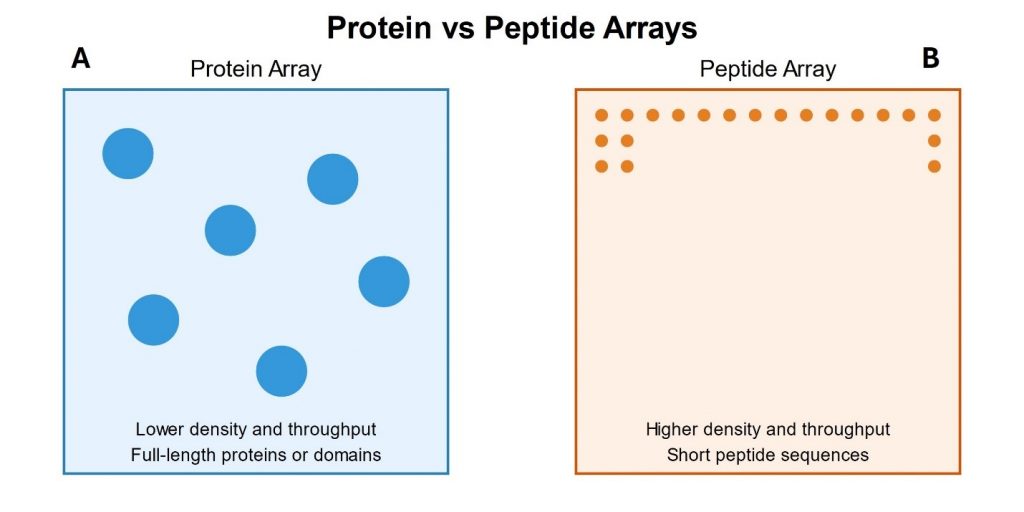

Protein arrays are tools that allow simultaneous analysis of thousands of proteins. These arrays consist of full-length proteins or protein domains immobilized on a solid support, typically a glass slide or a nitrocellulose membrane. Immobilized proteins retain their functional properties, enabling researchers to study various aspects of protein behavior in a high-throughput manner (Figure 1A).

There are several types of protein arrays, including:

- Analytical protein arrays: measure binding affinities, specificity, and protein expression levels.

- Functional protein arrays: study enzyme activities, protein-protein interactions, and protein-small molecule interactions.

- Reverse-phase protein arrays: analyze cell lysates or biofluids for the presence of specific proteins or post-translational modifications.

- Proteome arrays: used for high-throughput screening of protein-protein interactions, protein-drug interactions, and autoantibody profiling across a proteome [3,4].

The primary advantages of protein arrays lie in their high-throughput capabilities and parallelization of whole protein interaction studies. They offer the ability to simultaneously screen thousands of immobilized proteins against specific targets or to analyze multiple samples in parallel [4].

Peptide Arrays

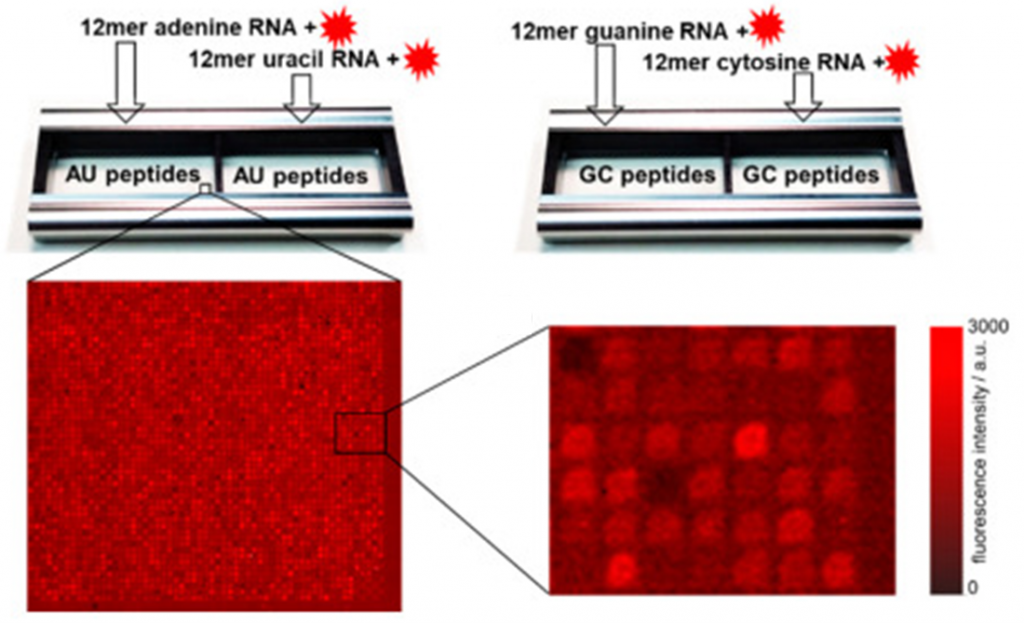

Peptide arrays consist of large numbers of different peptides arranged on a solid support. These peptides are typically short, ranging from 7 to 15 amino acids in length. Unlike protein arrays, peptide arrays focus on specific linear sequences rather than on the entire protein structure (Figure 1B) [5].

Peptide arrays can be further categorized based on their applications and design:

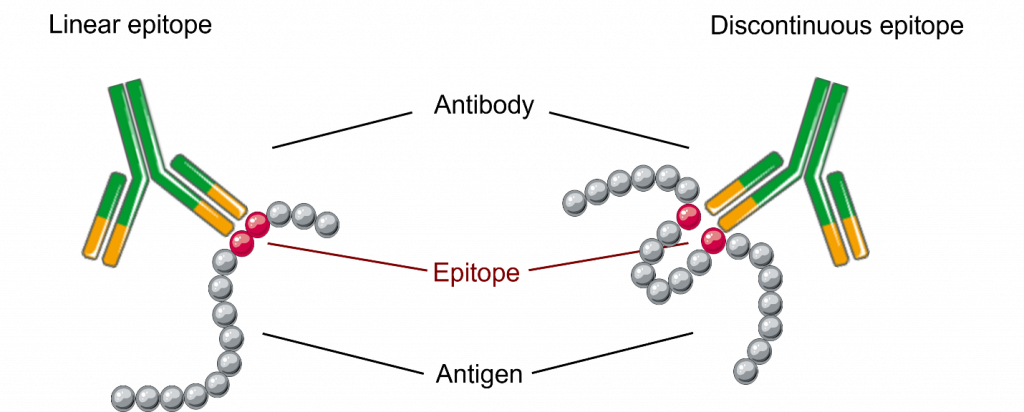

- Epitope mapping arrays: identify specific regions of proteins that antibodies recognize. Map epitopes along the length of a protein.

- Peptidome arrays: Represent the entire peptidome of an organism or a specific proteome subset. Used for comprehensive analysis of peptide-based interactions.

- Custom peptide arrays:

- Random peptide arrays: Used for unbiased screening of binding partners.

- Substitutional arrays: Systematically replace amino acids to study sequence-function relationships.

- Alanine scanning arrays: Replace each residue with alanine to identify critical amino acids for binding or function [6].

The key advantages of peptide arrays include their high density, and the ability to represent specific protein regions or motifs. They offer a targeted approach for studying protein interactions and are particularly useful for drug discovery and biomedical research.

Choosing between Protein and Peptide Arrays

The choice between protein and peptide arrays depends on the specific research question and experimental goals. Protein arrays are preferable for studying whole-protein interactions and analyzing complex samples. Peptide arrays are the better choice for mapping epitopes, screening large numbers of potential binding sequences, or when working with known interaction sites.

Table 1. Comparison of key aspects of protein and peptide arrays protein interaction assays [7,8].

| Aspect | Protein Arrays | Peptide Arrays |

|---|---|---|

| Size and Complexity | Full-length proteins or large domains | Short peptides (7-15 amino acids) that can cover entire protein sequences |

| Throughput | Typically, lower density (hundred to few thousand spots per array) | Very high density (can accommodate ten-hundreds of thousand spots per array) |

| Production and Scalability | More challenging; need to maintain protein structure and function during purification and immobilization | Easier to synthesize; can be produced at higher densities; more efficient and scalable |

| Applications | Whole-protein interactions, enzyme-substrate relationships, analysis of complex biological samples | Epitope mapping, investigating specific binding sites, screening for peptide-based drug candidates, systematic proteome scanning |

| Structural Information | Provide information about full protein structures, including conformational epitopes | Can infer information about larger structural elements and conformational epitopes through binding patterns of overlapping peptides |

| Coverage | Limited by the number of full-length proteins that can be produced and immobilized | Can achieve high-resolution coverage of entire proteomes through systematic peptide tiling |

| Sensitivity and Specificity | High specificity for intact protein interactions; may miss some weak or transient interactions | High sensitivity for detecting specific interaction sites; can identify both strong and weak binding regions |

| Resolution of Interaction Sites | Limited by the size of the full protein; cannot pinpoint exact binding sites | High-resolution; can pinpoint specific amino acid sequences involved in interactions |

| Speed of Production | Slower production due to protein expression and purification steps | Faster to produce; direct synthesis of peptides on array surface is relatively quick |

| Cost | Affordable for standardized libraries due to production and purification processes; very expensive for custom libraries | Affordable for standardized as well as custom libraries |

Conclusion

Protein and peptide arrays are powerful tools in proteomics. While protein arrays offer a view of full-length protein interactions, technological advances in peptide arrays have significantly enhanced their capabilities, allowing them to:

- Identify conformational epitopes by analyzing binding patterns across overlapping sequences.

- Provide insights into protein-protein interaction interfaces by mapping binding regions with high resolution.

- Detect weak or transient interactions that might be missed in full-length protein arrays owing to the higher sensitivity of peptide-based detection.

- Infer information about protein structure and folding patterns through systematic analysis of binding profiles.

These advancements allow peptide arrays to provide information comparable to protein arrays while retaining their inherent advantages of easier production, lower cost, and higher resolution in identifying specific interaction sites.

Axxelera offers cutting-edge peptide microarray solutions for many applications. Discover our peptide microarray solutions or contact us directly.

References

[1] Templin MF, Stoll D, Schrenk M, Traub PC, Vöhringer CF, Joos TO. Protein microarray technology. Drug Discov Today. 2002 Aug 1;7(15):815-22. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01910-2.

[2] Szymczak LC, Kuo HY, Mrksich M. Peptide Arrays: Development and Application. Anal Chem. 2018 Jan 2;90(1):266-282. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04380. Epub 2017 Dec 5. PMID: 29135227; PMCID: PMC6526727.

[3] Sutandy FX, Qian J, Chen CS, Zhu H. Overview of protein microarrays. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2013 Apr;Chapter 27(1):Unit 27.1. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2701s72.

[4] Zhu H, Bilgin M, Bangham R, Hall D, Casamayor A, Bertone P, Lan N, Jansen R, Bidlingmaier S, Houfek T, Mitchell T, Miller P, Dean RA, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Global analysis of protein activities using proteome chips. Science. 2001 Sep 14;293(5537):2101-5. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191.

[5] Katz C, Iosub-Amir A, Friedler A. Protein and Peptide Arrays. Encyclopedia of Biophysics. 2019; 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35943-9_189-1

[6] Katz C, Levy-Beladev L, Rotem-Bamberger S, Rito T, Rüdiger SG, Friedler A. Studying protein-protein interactions using peptide arrays. Chem Soc Rev. 2011 May;40(5):2131-45. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00029a.

[7] Forsström B, Axnäs BB, Stengele KP, Bühler J, Albert TJ, Richmond TA, Hu FJ, Nilsson P, Hudson EP, Rockberg J, Uhlen M. Proteome-wide epitope mapping of antibodies using ultra-dense peptide arrays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014 Jun;13(6):1585-97. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.033308.

[8] Legutki JB, Zhao ZG, Greving M, Woodbury N, Johnston SA, Stafford P. Scalable high-density peptide arrays for comprehensive health monitoring. Nat Commun. 2014 Sep 3;5:4785. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5785.